Louisiana French (French: français de la Louisiane, Louisiana Creole: françé la lwizyàn), also known as Cajun French (French: français cadien/français cadjin) is a variety of the French language spoken traditionally in colonial Lower Louisiana but as of today it is primarily used in the U.S. state of Louisiana, specifically in the southern parishes, though substantial minorities exist in southeast Texas as well. It comprises several distinct varieties, each incorporating some words of African, Spanish, Native American and English origin, sometimes giving it linguistic features found only in Louisiana, but it remains mutually intelligible with other forms of the French language. Figures from the United States Census record that roughly 3.5% of Louisianans over the age of 5 report speaking French or a French-based creole at home.

The language is spoken across ethnic and racial lines by people who identify as Cajun, as Louisiana Creole as well as Chitimacha, Houma, Biloxi, Tunica, Choctaw, Acadian, and French among others. For these reasons, the label Louisiana French or Louisiana Regional French is generally regarded as more accurate and inclusive than "Cajun French" and is the preferred term of linguists and anthropologists. However, "Cajun French" is commonly used in lay discourse by speakers of the language and other inhabitants of Louisiana.

Parishes in which these dialects are still found include but are not limited to Acadia, Ascension, Assumption, Avoyelles, Cameron, Evangeline, Iberia, Jefferson Davis, Lafayette, Lafourche, St. Martin, St. Mary, Terrebonne, Pointe Coupée, Vermillion, and other parishes of Southern Louisiana.

Louisiana French should further not be confused with Louisiana Creole, a distinct French-based creole language indigenous to Louisiana and spoken across racial lines. In Louisiana, language labels are often conflated with ethnic labels. For example, a speaker who identifies as Cajun may call their language "Cajun French", though linguists would identify it as Louisiana Creole.

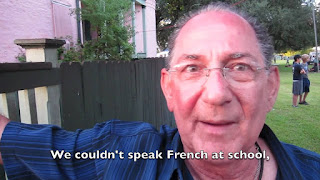

Video Louisiana French

History

Starting in the second half of the seventeenth century several trading posts were established in Lower Louisiana (French: Basse-Louisiane) eventually giving way to greater French colonial aspirations with the turn of the century. French immigration was at its peak during the 17th and 18th centuries which firmly established the Creole culture and language there. One important distinction to make is that the term "créole" at the time was consistently used to signify native, or "locally-born" in contrast to "foreign-born". In general the core of the population was rather diverse, coming from all over the French colonial empire namely Canada, France, and the French West Indies.

Eventually, with the consistent relations built between the Native American tribes and francophones, new vocabulary was eventually adopted into the colonial language. For example, something of a "French-Choctaw patois" is said to have developed primarily among Louisiana's Afro-French population and métis Creoles with a large portion of its vocabulary said to be of Native American origin. Prior to the late arrival of the Acadian people in Louisiana, the French of Louisiana had already begun to undergo changes as noted by Captain Jean-Bernard Bossu who traveled with and witnessed by Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne speaking this "common language." This unusual blend of French was also noticed by Pierre-Clement de Laussat during a lunch visit with the Creole-French Canterelle family. Upon arrival of their Houma relatives, the family began conversing in "French and Choctaw." Additional witness to this variety of French comes from J.F.H. Claiborne, a cousin of Louisiana's first American Governor, who also noted the "unusual patois of provincial French and Choctaw."

Starting in 1755, large populations of the French-speaking Acadians began to arrive en masse along the Mississippi River as well as making all the way to south to Louisiana following the Great Upheveal bringing their own influence to the region. In 1762, France relinquished their territorial claims to Spain just has Acadians had begun to arrive in Louisiana; despite this, Spanish Governor Bernardo de Gálvez, permitted the Acadians to continue to speak their language as well as observe their other cultural practices. The original Acadian community was composed mainly of farmers and fishermen who were able to provide their children with a reasonable amount of schooling. However, the hardships after being exiled from Nova Scotia, along with the difficult process of resettlement in Louisiana and the ensuing poverty, made it difficult to establish schools in the early stages of the community's development. Eventually schools were established, as private academies whose faculty had recently arrived in Louisiana from France or who had been educated in France. Children were usually able to attend the schools only long enough to learn counting and reading. At the time, a standard part of a child's education in the Cajun community was also the Catholic catechism, which was taught in French by an older member of the community. The educational system did not allow for much contact with Standard French. It has often been said that Acadian French has had a large impact on the development of Louisiana French but this has generally been over-estimated.

French immigration continued in the 19th century until the start of the American Civil War, bringing large numbers of francophones speaking something more similar to today's Metropolitan French to Louisiana. Over time, through contact between different ethnic groups the various dialects converged to produce what we know as Louisiana French.

Decline

The strong influence of English-language education on the francophone community began following the American Civil War, when laws that had protected the rights of French speakers were abolished. Public schools that attempted to force francophones to learn English were established in Louisiana. Parents viewed the practice of teaching their children English as the intrusion of a foreign culture, and many refused to send their children to school. When the government required them to do so, they selected private French Catholic schools in which class was conducted in French. The French schools worked to emphasize International French, which they considered to be the prestige dialect. When the government required all schools, public and parochial, to teach in English, new teachers, who could not speak French, were hired. Children could not understand their teachers and generally ignored them by continuing to speak French. Eventually, children became punished for speaking French on school grounds.

Many question whether the Louisiana French language will survive another generation. Some residents of Acadiana are bilingual though, having learned French at home and English in school. The number of speakers of Louisiana French has diminished considerably since the middle of the 20th century, but efforts are being made to reintroduce the language in schools.

The punishment system seems to have been responsible for much of the decay that Louisiana French experienced in the 20th century since, in turn, people who could not speak English were perceived as uneducated. Therefore, parents became hesitant to teach French to their children, hoping that the children would have a better life in an English-speaking nation.. As of 2011, there are an estimated 150,000 to 200,000 people in Louisiana who speak French. By comparison, there were an estimated one million native French-speakers in Louisiana in about 1968. The dialect is now at risk of extinction as children are no longer taught it formally in schools.

Currently, Louisiana French is considered an endangered language.

Preservation efforts

Marilyn J. Conwell of Pennsylvania State University conducted a study of Louisiana French in 1959 and published "probably the first complete study of a Louisiana French dialect," Louisiana French Grammar, in 1963. Conwell focused on the French spoken in Lafayette, Louisiana and evaluated what was then its current status. Conwell pointed out that the gradual decline of French made it "relatively common" to find "grand-parents who speak only French, parents who speak both French and English, children who speak English and understand French, and grand-children who speak and understand only English." The decision to teach French to children was well-received since grandparents hoped for better opportunities for communicating with their grandchildren.

The Council for the Development of French in Louisiana (CODOFIL) was established in 1968 to promote the preservation of French language and culture in Louisiana. In addition to this, some Louisiana universities, such as LSU, offer courses in "Cajun French" in the hopes of preserving the language.

Many young adults are learning enough French to understand French music lyrics. Also, there is now a trend to use the French language websites to learn the dialect. Culinary words and terms of endearment such as "cher" /?æ/ (dear) and "nonc" (uncle) are still heard among otherwise English-speaking Louisianians.

The Louisiana state legislature has greatly shifted its stance on the status of French. Since the passage of Legislative Act No. 409 in 1968, the Louisiana governor is granted the authorization "to establish the Council for the Development of Louisiana-French" and that the agency is to consist of no more than fifty members, including a chairman. The name was soon changed to CODOFIL and was granted the power to "do anything possible and necessary to encourage the development, usage and preservation of French as it exists in Louisiana.

In 1984, Jules O. Daigle, a Roman Catholic priest, published A Dictionary of the Cajun Language the first dictionary devoted to "Cajun French." Once considered an authority on the language, it is not exhaustive; it omits alternate spellings and synonyms that Father Daigle deemed "perversions" of the language but are nonetheless popular among so-called Louisiana French speakers and writers. Though remaining useful today, Daigle's dictionary has been superseded by the Dictionary of Louisiana French (2010), edited by Albert Valdman and other authorities on the language.

Beginning in the 1990s, when cultural and ethnic tourism proved a lucrative enterprise, various signage, packaging, and documentation in French became visible throughout the state. State and local tourism bureau commissions were influential in convincing city, parish and state officials to produce bilingual signage and documentation. French and English bilingual signage is, therefore, usually confined to the old districts of cities, like the French Quarter in New Orleans, downtown Lafayette, New Iberia (trilingual with Spanish), St. Martinville, Breaux Bridge, and several other cities. Locals continue to refer to the place names in English and for postal services the English version is generally preferred. To meet the demands of a growing francophone tourist market, tourism bureaus and commissions throughout the state, particularly in southern Louisiana, have information on tourist sites in both French and English as well as in other major languages spoken by tourists.

An article written online by the Université Laval argues that the state of Louisiana's shift, from an anti-French stance to one of soft promotion has been of great importance to the survival of the language. The article states that it is advantageous to invigorate the revival of the language to better cherish the state's rich heritage and to protect a Francophone minority that has suffered greatly from negligence by political and religious leaders. Furthermore, the university's article claims that it is CODOFIL and not the state itself that sets language policy and that the only political stance the state of Louisiana makes is that of noninterference. All of this culminates in the fact that outside the extreme southern portions of the state, French remains a secondary language that retains heavy cultural and identity values.

According to Jacques Henry, former executive director of CODOFIL, much progress has been made for francophones and that the future of French in Louisiana is not merely a symbolic one. According to statistics gathered by CODOFIL, the past twenty years has seen widespread acceptance of French-immersion programs. He goes further to write that the official recognition, appreciation by parents, and inclusion of French in schools reflects growing regard of the language and that ultimately the survival of French in Louisiana will be guaranteed by Louisianan parents and politicians, stating that Louisiana French's survival is by no means guaranteed but that there is still hope.

Similarly, the state legislature passed the Louisiana French Language Services Act in 2011 with particular mention to cultural tourism and local culture and heritage. The bill sets forth that each branch of the state government shall take necessary action to identify employees who are proficient in French. Each branch of the state government is to take necessary steps in producing services in the Louisiana French language for both locals and visitors. This bill is, however, an unfunded state mandate. The legislative act was drafted and presented by francophone and francophile senators and representatives as it asserts that the French language is vital to the economy of the state.

Maps Louisiana French

Population

Reliable counts of speakers of Louisiana French are difficult to obtain as distinct from other varieties of French. However, the vast majority of native residents of Louisiana and east and southeast Texas who speak French would be considered speakers of Louisiana French.

In Louisiana, as of 2010, the population of French speakers was approximately 115,183. These populations are concentrated most heavily in the southern, coastal parishes.

In Texas, as of 2010, the French-speaking population was 55,773, though many of these were likely immigrants from France and other locations in the urban areas. Nevertheless, in the rural eastern/southeastern Texas counties of Orange, Jefferson, Chambers, Newton, Jasper, Tyler, Liberty, and Hardin alone--areas where it can be reasonably presumed that almost all French speakers are Louisiana French speakers--the total French-speaking population was composed of 3,400 individuals. It is likely a substantial portion of the 14,493 speakers in Houston's Harris county are also Louisiana French speakers. With this is mind, a marked decline in the number of French speakers in Texas has been noticed in the last half of the twentieth century. For example, at one point the French-speaking population of Jefferson County, for example was 24,049 as compared to the mere 1,922 today. Likewise in Harris County the French-speaking population has shifted from 26,796 to 14,493 individuals.

Louisiana French-speaking populations can also be found in southern Mississippi and Alabama, as well as pockets in other parts of the United States.

Grammar

Despite ample time for Louisiana French to diverge, the basic grammatical core of the language remains similar or the same as Standard French. Even so, it can be expected that the language would begin to diverge due to the various influences of neighboring languages, changing francophone demographics, and unstable opportunities for education. Furthermore, Louisiana French lacks any official regulating body unlike that of Standard French or Quebec French to take part in standardizing the language.

Pronouns

1. eusse/euse is confined to the southeastern parishes of Louisiana

Immediately some distinct characteristics of Louisiana French can be gleaned from its personal pronouns. For example, the traditional third-person singular feminine pronoun elle of Standard French is present but also the alternative of alle which is chosen by some authors since it more closely approximates speakers' pronunciation. Also use of the pronoun ils has supplanted the third-person feminine pronoun elles as it is used to refer to both masculine and feminine subjects. Similarly, all of the other third-person plural pronouns are also neutral.

Verbs

Contractions

In Informal Louisiana French, contractions are often absent:

- J'ai appris de les grand-parents

(I learned from the grandparents) instead of standard J'ai appris des grand-parents.

- La lumière de le ciel (the skylight) instead of standard La lumière du ciel.

Proper Names

Place names in Louisiana French usually differ from those in International French. For instance, locales named for American Indian tribes usually use the plural article, les, before as name instead of the masculine or feminine singular article le/la. Likewise, movement towards those locations uses the plural, aux, before the place name. That varies by region. In Pierre Part, Louisiana, for example, elderly francophones have often been heard to say la Californie, le Texas, la Floride. People in Lafayette, Louisiana, also use articles in front of the state names.

In Informal Louisiana French, most US states and countries are pronounced as in English and therefore require no article: California, Texas, Florida, New York, New Mexico, Colorado, Mexico, Belgium, Morocco, Lebanon, et cetera. In Formal Louisiana French, prefixed articles are absent, in contrast to International French: Californie, Texas, Floride, Belgique, Liban, et cetera.

Vocabulary

From a lexical perspective, Louisiana French differs little from other varieties of French spoken in the world. However, there are several lexical treats stemming from many linguistic origins; some are unique to Louisiana French while others are shared sporadically throughout the Francophone world.

Code-switching and Lexical Borrowing

Code-switching occurs frequently in Louisiana French but this is typical for many language contact situations. Code-switching was once viewed as a sign of poor education, but it is now understood to be an indication of proficiency in the two different languages that a speaker uses. Fluent Louisiana French speakers frequently alternate from French to American English, but less proficient speakers will usually not.

English influences

1. Il y avait une fois il drivait, il travaillait huit jours on et six jours off. Et il drivait, tu sais, six jours off. Ça le prendrait vingt-quatre heures straight through. Et là il restait quatre jours ici et il retournait. So quand la seconde fois ç'a venu, well, il dit, "Moi, si tu viens pas," il dit, "je vas pas." Ça fait que là j'ai été. Boy! Sa pauvre mère. "Vas pas!"

One time he was driving, he was working eight days on and six days off. And he was driving, y'know, six days off. It would take him twenty-four hours straight through. And he would stay here four days and then go back. So when the second time came, well, he said, "If you don't come," he said, "I'm not going." So I went. Boy! His poor mother. "Don't go!" she said. "Don't go!"

2. Le samedi après-midi on allait puis...wringer le cou de la volaille. Et le dimanche, well, dimanche ça c'était notre meilleure journée qu'on avait plus de bon manger. Ma mère freezait de la volaille et on avait de la poutine aux craquettes.

Saturday afternoon we would go...wring the chicken's neck. And on Sunday, well, Sunday, that was our best day for eating well. My mother would freeze some chicken and we would have some poutine of croquettes.

Creole influences

Francophones and creolophones have worked side-by-side, lived among one another, and have enjoyed local festivities together throughout the history of the state. As a result, in regions where both Louisiana French and Louisiana Creole are or used to be spoken, the inhabitants of the region often code-switch, beginning the sentence in one language and completing it in another.

Taxonomy

Taxonomies for classing Louisiana French have changed over time. Until the 1960s and 1970s, Louisianans themselves, when speaking in French, referred to their language as français or créole. In English, they referred to their language as "Creole French" and "French" simultaneously.

In 1968, Lafayette native James Domengeaux, a US Representative, created the Council for the Development of French in Louisiana (CODOFIL), whose mission was to oversee the promotion, visibility and expansion of French language usage in Louisiana. His mission was clear: (re)create a European French bastion in Louisiana by making all Louisianans bilingual in International French and English. To accomplish his goals, he teamed up with political leaders in Canada and France, including former French President Georges Pompidou. He found Louisiana French too limiting, so he imported francophone teachers from Europe, Canada and the Caribbean to teach normative French in Louisiana schools. His penchant for International French caused him to lose support in Louisiana: most Louisianans, if they were going to have French in Louisiana schools, wanted Louisiana French, not "Parisian French."

Simultaneously, an ethnic movement took root in South Louisiana led by Acadian-Creoles like James Donald Faulk, Dudley Joseph Leblanc and Jules O. Daigle. Faulk, a French teacher in Crowley, Louisiana, introduced using the term "Cajun French" for Acadian-Creoles and French Creoles who identified as Cajun, for which he created a curriculum guide for institutionalizing the language in schools in 1977. Roman Catholic Priest Jules O. Daigle, who in 1984 published his Dictionary of the Cajun Language, followed him. "Cajun French" is intended to imply the French spoken in Louisiana by descendants of Acadians, an ethnic qualifier rather than a linguistic relationship.

In 2009, Iberia Parish native and activist Christophe Landry introduced three terms representing lexical differences based on Louisiana topography: Provincial Louisiana French (PLF), Fluvial Louisiana French (FLF) and Urban Louisiana French (ULF). That same year, the Dictionary of Louisiana of Louisiana French, subtitled "as spoken in Cajun, Creole and American Indian communities," was published. It was edited by a coalition of linguists and other activists. The title clearly suggests that the ethno-racial identities are mapped onto the languages, but the language, at least linguistically, remains shared across those ethno-racial lines.

Due to present ethnic movements and internal subdivisions among the population, some of the state's inhabitants insist are ancestral varieties. As a result, it is not odd to hear the language referred to as Canadian French, Acadian French, Broken French, Old French, Creole French, Cajun French, and so on. Still other Louisiana francophones will simply refer to their language as French, without qualifiers. Internally, two broad distinctions will be made: formal Louisiana French and informal Louisiana French.

Varieties

Informal Louisiana French

Known more commonly as informal Louisiana French or as Provincial Louisiana French, this variety of Louisiana French has its roots in agrarian Louisiana, but it is now also found in urban centers because of urbanization beginning in the 20th century.

Historically, along the prairies of southwest Louisiana, francophone Louisianans were cattle grazers as well as rice and cotton farmers. Along the bayous and the Louisiana littoral, sugar cane cultivation dominated and in many parishes today, sugar cultivation remains an important source of economy (like in Iberia and St. Martin parishes).

In this variety, R is alveolar, not guttural, the AU in words becomes /aw/, and the vowels at the beginning and end of words are usually omitted (Américain changes to Méricain, Espérer to Spérer). Likewise, É preceding an O frequently disappears in spoken informal LF all together (Léonide changes to Lonide, Cléophas to Clophas).

The nasality and pitch is akin to pitch and intonation associated with provincial speech in Québec. In terms of nasality, Louisiana French is similar to French spoken in Brussels, Paris and Dakar (Senegal). Among the varieties such as those is, however, a difference in stress (inflection, accentuation), rhythm (cadence and lilt), articulation, timbre (character and quality of each phoneme, or sound), form and sound fluctuations (modulation), and tone (intonation). The pitch of PLF and Provincial Quebec French (PQF) share a predominantly agricultural history, close contact with pre-Columbian peoples and relative isolation from urbanized populations.

Bayou Lafourche

Particular mention should be made to the francophones of Bayou Lafourche. An interesting linguistic phenomenon here that is absent everywhere else in Louisiana. Some francophones along Bayou Lafourche pronounce the G and J in French as the English letter H (like in most Spanish dialects), but others pronounce the two letters in the manner of most other francophones.

Two theories exist to explain the feature. On the one hand, some activists and linguists attribute this feature to an inheritance of Acadian French spoken in Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and other Canadian maritime provinces, a theory based entirely on observation of shared vocal features rather than the communities being linked by migration.

On the other hand, it has been suggested that there may be a linguistic link to the hispanophones living at the Mississippi River and Bayou Lafourche junction, who were more numerous than the Acadians in the immediate vicinity.

Interestingly, the Louisiana Creole spoken in Lafourche Parish in and around Kraemer, Choctaw, Bayou Boeuf and Chackbay contains the letters G and J, but they are voiced as they are in LC spoken elsewhere in the state and as the French spoken elsewhere, not as the aspirated Hs in Lower Bayou Lafourche French.

Formal Louisiana French

Formal French is the language used in all administrative and ecclesiastic documents, speeches and in literary publications. Also known as Urban Louisiana French (ULF), it is spoken in the urban business centers of the state. Those regions have historically been centers of trade, commerce and contact with speakers of French from Europe. It would include New Orleans and its environs, Baton Rouge and its environs, St. Martinville (here, along class lines) and other once important Francophone business centers in the state. ULF sounds almost identical to Standard French, with pronunciation and intonation varying from European to North American.

Community

French language masses in Louisiana

- Our Lady of Fatima Roman Catholic Church, Lafayette, Louisiana

- St Martin de Tours Roman Catholic Church, St. Martinville, Louisiana

Healing practices

Medicine men and women, or healers (French: traiteur/traiteuse), are still found throughout the state. During their rituals for healing, they use secret French prayers to God or saints for a speedy recovery. These healers are mostly Catholic and do not expect compensation or even thanks, as it is said that then, the cure will not work.

Recurring French language festivities/events

- Festival International de Louisiane, April, Lafayette, Louisiana

- Festivals Acadiens Et Créoles, October, Lafayette, Louisiana

- ALCFES (Association louisianaise des clubs français des écoles secondaires)

- Francophone Open Microphone, Houma, Louisiana

- La table française, Dwyer's Café, Jefferson Street, Lafayette, Louisiana

- La table française, Arnaudville, Louisiana

- La table française, La Madeleine, Baton Rouge, Louisiana

- Creole Families Bastille Day Heritage Festival, Ville Platte, Louisiana weekend of July 14, Civic Center

- French film: Nuit blanche à Bâton-Rouge, Louisiana State University Center for French and Francophone Studies, Baton Rouge, Louisiana [2]

- Rendez-vous des Cajuns, Liberty Theater, Eunice, Louisian

Music

Louisiana French has been the traditional language for singing music now referred to as Cajun, zydeco, and Louisiana French rock. Today, Old French music, Creole stomp, and Louisiana French rock remain the only three genres of music in Louisiana using French instead of English. In "Cajun", most artists have expressions and phrases in French in songs, predominantly sung in Louisiana English.

Media

French on Louisiana radio stations

- KRVS 88.7:, Radio Acadie University of Louisiana at Lafayette, Lafayette, Louisiana

- KBON 101.1 FM: Louisiana Proud, Eunice, Louisiana

- KLEB 1600 AM: Golden Meadow, Louisiana

- KLRZ 100.3 FM: Rajun' Cajun Larose, Louisiana

- KJEF 1290 AM Cajun Radio, Jennings, Louisiana

- KLCL 1470 AM Cajun Radio, Lake Charles, Louisiana

- KVPI 1050 AM, Ville Platte, Louisiana

- KVPI 92.5 FM, Ville Patte, Louisiana

French periodicals, newspapers, and publications

- Les éditions Tintamarre, Centenary College of Louisiana, Shreveport, Louisiana.

- La revue louisianaise, University of Louisiana Lafayette.

- La revue de la Louisiane, now defunct, was the journal launched by James R. Domengeaux.

French on Louisiana cable networks

- TV5 Monde

- Louisiana Public Broadcasting (LPB)

- Rosaries in French, KLFY TV10, Lafayette

Education

French-language Public School Curriculum (French Immersion)

As of autumn 2011, Louisiana has French-language total immersion or bilingual French and English immersion in ten parishes: Calcasieu, Acadia, St. Landry, St. Martin, Iberia, Lafayette, Assumption, East Baton Rouge, Jefferson and Orleans. Students placed in the program begin in kindergarten or first grade and continue until high school.

The curriculum in both the total French-language immersion as well as in the bilingual program follows the same standards as all other schools in the parish and state.[3][4]

The Council for the Development of French in Louisiana (CODOFIL) recruits teachers locally and globally each year. Les Amis de l'Immersion, Inc. is the parent-teacher organization for students in French immersion in the state. Les Amis organizes summer camps, fundraisers and outreach for teachers, parents and students in the program.

The immersion programs as of autumn 2011 are as follows:

CODOFIL Consortium of Louisiana Universities and Colleges

The Consortium of Louisiana Universities and Colleges unites representatives of French programs in Louisiana universities and colleges, and organizes post-secondary level Francophone scholastic exchanges and provide support for University students studying French language and linguistics in Louisiana. Member institutions include these:

- Centenary College of Louisiana, Shreveport

- Delgado Community College, New Orleans, Louisiana

- Dillard University, New Orleans

- Grambling State University, Grambling, Louisiana

- Louisiana College, Pineville, Louisiana

- Louisiana State University (Alexandria, Baton Rouge, Eunice, Shreveport)

- Louisiana Tech University, Ruston, Louisiana

- Loyola University, New Orleans

- McNeese State University, Lake Charles, Louisiana

- Nicholls State University, Thibodaux, Louisiana

- Northwestern State University, Natchitoches, Louisiana

- Our Lady of Holy Cross College, New Orleans

- Southeastern Louisiana University, Hammond, Louisiana

- Southern University at Baton Rouge, Baton Rouge, Louisiana

- Southern University at New Orleans, New Orleans

- Tulane University, New Orleans

- University of Louisiana at Lafayette

- University of Louisiana at Monroe

- University of New Orleans, New Orleans

- Xavier University of Louisiana, New Orleans

Notable Louisiana French-speaking people

- Barry Jean Ancelet

- Calvin Borel

- Michael Doucet

- Canray Fontenot

- Richard Guidry

- Stephen Ortego

- Glen Pitre

- Zachary Richard

- Mabel Sonnier Savoie

- Sybil Kein

- John LaFleur II

- Christophe Landry

- Rosie Ledet

- Boozoo Chavis

- Clifton Chenier

- John Delafose

- C.J Chenier

- Ambrose Sam

See also

- List of Louisiana parishes by French-speaking population

- Louisiana Creole

- Acadian French

- Canadian French

- Haitian French

- American French

References

Further reading

- Malveaux, Vivian (2009). Living Creole and Speaking It Fluently. AuthorHouse.

- laFleur II, John; Costello, Brian (2013). Speaking In Tongues, Louisiana's Colonial French, Creole & Cajun Languages Tell Their Story. BookRix GmbH & Co. KG.

- Valdman, Albert; et al. (2009). Dictionary of Louisiana French: As spoken in Cajun, Creole and American Indian communities. University Press of Mississippi.

- Picone, Michael D. (1997). "Enclave Dialect Contradiction:German words". American Speech. Duke University Press. 72 (2): 117-153. doi:10.2307/455786.

- Cajun French Dictionary and Phrasebook by Clint Bruce and Jennifer Gipson ISBN 0-7818-0915-0. Hippocrene Books Inc.

- Tonnerre mes chiens! A glossary of Louisiana French figures of speech by Amanda LaFleur ISBN 0-9670838-9-3. Renouveau Publishing.

- A Dictionary of the Cajun Language by Rev. Msgr. Jules O. Daigle, M.A., S.T.L. ISBN 0-9614245-3-2. Swallow Publications, Inc.

- Cajun Self-Taught by Rev. Msgr. Jules O. Daigle, M.A., S.T.L. ISBN 0-9614245-4-0. Swallow Publications, Inc.

- Language Shift in the Coastal Marshes of Louisiana by Kevin J. Rottet ISBN 0-8204-4980-6. Peter Lang Publishing, Inc.

- Conversational Cajun French I by Harry Jannise and Randall P. Whatley ISBN 0-88289-316-5. The Chicot Press.

- Dictionary of Louisiana French as Spoken in Cajun, Creole, and American Indian Communities, senior editor Albert Valdman. ISBN 978-1-60473-403-4 Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2010.

External links

- Allons! An Introduction to Louisiana French

- Creole Poems

- Centenary University Bibliothèque Tintamarre Texts in Louisiana French

- NOLA Francaise

- Le bijou sur le Bayou Teche

- We speak French in French Louisiana

- [5]LSU Cajun Pages

- [6]A beginner's introduction: What is Cajun French?

- [7]Le français cadien par thèmes: Cajun French by Themes

- [8]Faux amis: How to Speak French in Louisiana Without Getting in Trouble

- [9]Glossaire Français Cadien-Français Européen: Cajun-Standard French Glossary

- [10]L'interrogatif en français cadien: Forming questions in Cajun French

- [11]Les pronoms personnels cadiens: Cajun personal pronouns

- [12]Les pronoms sujets et le système verbal: The Basics of Verb Conjugation

- [13]Les animaux dans la métaphore populaire: Cajun animal metaphors

- [14]Un glossaire cadien-anglais: Cajun French to English glossary

- [15]La Base de données lexicographiques de la Louisiane

- [16]TVTL.tv Télévision Terrebonne-LaFourche

- [17]Council for the Development of French in Louisiana (CODOFIL)

- [18]Cajun language websites

- [19]Cane River Valley French

- [20]Cajun French Language Tutorials

- [21]Terrebonne Parish French Online!

- [22]Cajun French Virtual Table Francaise

Source of article : Wikipedia